|

Westport Historical

Footnotes An historical

tidbit archive of general interest to all Westporters. Sponsored by EverythingWestport.com Click

on photos to enlarge (if applicable.) |

|

|

|

|

|

“Stove Boats, Shipwrecks and Cannibalism – the perils of 19th

century whaling.” Thursday, October 20, 2016

Photos |

EverythingWestport.com “Stove Boats, Shipwrecks and

Cannibalism” was the formal title of an October 20th

lecture by Westport Historical Society president Tony Connors on the perils

that faced local sailors who shipped out for long, hard voyages on Westport

whalers during the 19th century. The

catchy title referred to only a few of the many dangers faced by the captains

and crews of the whaleships that called Westport Point their home port, and

made their hometown known all over the world. Connors started out his talk with a historic

overview of the whaling industry, an important part of the local economy

between the years 1803 and 1879. Westport Point was ranked eighth among the

most successful whaling ports of that era, sending dozens of its ships around

the globe in search of whales; nearby New Bedford was the top-grossing home

port of the worldwide whaling industry, and quite a few Westport captains

skippered those whaleships. Westporters had been involved in small scale

whaling close to shore since colonial times, but got seriously involved in

the growing whaling industry as the 1800s got

underway. “The last (whaling) ship went out of Westport in 1879,” Connors

noted. |

|

|

A glimpse into 20th century

rum-running in Westport. Wednesday, May 07,

2014 Westport’s Cukie Macomber shares a memory on the town’s rum-running

days.

Rumrunners included local fishermen, boat

owners and other local lawbreakers who transported whiskey and rum from large

ships anchored in Rum Row, an area outside territorial waters located 3 miles

from shore at first, but then increased to 11 miles. Small powerboats loaded

up the cargo and proceeded to rush to shore without meeting up with a Coast

Guard ship. Most of the locals’ small boats were faster than the Coast Guard

vessels so many, many of the rumrunners avoided arrest. I knew a pair of rumrunners, one of whom

became very famous. Charlie Travers was a young, intelligent man

who saw rum running as an opportunity to get rich. And he did. Charlie had a

boat called “Black Duck” built at Casey Boatyard. It was 50-feet long and

powered by two airplane engines.

Aircraft engines were made for high RPMs—perfect for a rum-running

vessel. Black Duck was capable of doing 30 knots

that was unheard of for a smallish boat. One night, “the Duck” entered Narragansett

Bay when it came upon a Coast Guard cutter moored to a bell buoy. The ship’s

searchlight illuminated Travers’ boat and her crew. After some crazy

maneuvering by Charlie’s helmsman, the Coast Guard opened fire with a machine

gun. The gunner had orders to shoot into the

stern of the Duck but instead got carried away and swept the pilothouse

killing a trio of crewmembers. When word got out, angry crowds protested

outside government buildings all over the United States. Their cry was that

the country’s military killed unarmed civilians. Investigations were launched and finally the

Secretary of the Treasury— who was also head of the Coast Guard— stated that the killings were

justified. Put out of the rum-running business by the tragedy at sea, Charlie

retired to his dairy farm where he helped many people survive the Great

Depression. I remember the Black Duck—the rum-runner powered by airplane

engines— retired to a special dock Charlie had built in the Westport River.

According to other sources, the Black Duck was retrofitted by the Coast Guard

into a patrol boat that scoped out rumrunners along the Westport coast.” Editor’s note: The Westport Historical Society had a

presentation on September 26, 2013 where a panel of four people monitored by

noted Westport author Dawn Tripp provided a fascinating glimpse into

rum-running in Westport during Prohibtion.

Above, left:

Westport Harbormaster, Richie Earle displays one of many unstamped liquor

bottles still containing its contents found in the Westport River from the

town’s early rum-running days. Right: Westport defacto historian

Cukie Macomber relates his story of the ‘Black Duck’ with Dawn Tripp. Photos: EverythingWestport.com. |

|

|

Who

was Charlotte White?

Wednesday,

December 18, 2013 Presented by Tony Connors, President, Westport Historical Society. We see her name

on the street sign in the center of Westport: Charlotte White Road. She is

mentioned in local history books as a healer, a midwife, a poet. But what do

we really know about Charlotte White? Let's start with

her name. The typical pronunciation of the name Charlotte is "Shar-lot" but there is a local oral tradition that

it was pronounced "Sha-lot-ee." How did Charlotte

herself pronounce her name? The first clue was found a few years ago when the

late Bill Wyatt, former president of the Historical Society, was researching

the 19th-century account books of the Westport physicians Eli and James

Handy. Bill found an entry for "Charlotty

White," a phonetic spelling of her name that indicates a three-syllable

pronunciation. The second clue

can be found in the town records regarding early poor relief in Westport.

Several town records from 1812-1813 refer to her as "Cholata"

White, which drops the "r" (as most locals from Massachusetts and

Rhode Island do) and flattens the final "e" to "ah," but

clearly shows the three-syllable form. Based on this evidence, it is most

likely she was called "Sha-lot-ah." Charlotte White

was born in 1774 or 1775, depending on the source. Her mother, Elizabeth

(David) White (1730-1827) was Native American — a Wampanoag, most likely from

Martha's Vineyard. Her father (whose dates are unknown) was a former slave

variously referred to as Zip, Sip, Zilpiah, or Zephriah. He apparently belonged at one time to the

Lawton family but was later owned by George White, the son of Elizabeth

Cadman White and William White, the original owners of the Cadman-White-Handy

House on Hixbridge Road. “Charlotte was

connected to Westport's well-known mariner, philanthropist, and black rights

advocate Paul Cuffe (1759-1817). They both had a

Wampanoag mother and an African father who had been a slave. Charlotte's

sister Jane married John Cuffe, Paul's brother.

There are also numerous links between Charlotte and the Wainer

family, who were in-laws and business partners of Paul Cuffe.” Tony Connors, WHS Elizabeth and Zip

married in 1765, while he was still a slave (he obtained his freedom on March

25, 1766), and had a house on what is now Charlotte White Road. In addition

to Charlotte, they had a daughter Jane. It appears that Charlotte did not

marry; she is listed in one census as a "colored maiden." In the Historical

Society collection is one poem by Charlotte White, but her poetry — at least

what we know of it — is not very original. For example, the lines

"Charlotte White is my name/ and New England is my nation./ Westport is my dwelling place/ and Heaven is my

salvation" are only a variation of a well-known form: "Anytown is my dwelling-place/ America is my nation/ John

Smith is my name/ And heaven my expectation." While this may

not be particularly good poetry, it does show that Charlotte had some degree

of education, and had an interest — and some skill — in language. Some Interesting Connections Charlotte was

connected to Westport's well-known mariner, philanthropist, and black rights

advocate Paul Cuffe (1759-1817). They both had a

Wampanoag mother and an African father who had been a slave. Charlotte's

sister Jane married John Cuffe, Paul's brother.

There are also numerous links between Charlotte and the Wainer

family, who were in-laws and business partners of Paul Cuffe. A recently

unearthed newspaper article from the 1940s links Charlotte to another

noteworthy Westport native, Perry Davis. Davis (1791-1862) had a hard-luck

life. He was badly hurt falling off a roof at age 14. The business he had

established in Fall River was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1843, and a

later explosion left him badly burned. But he eventually achieved great

success as the manufacturer of Perry Davis Pain Killer, one of the best-selling

patent medicines of the 19th century. The success was largely due to his

secret formula of vegetable extracts, alcohol, and opium. In the newspaper

article, Elizabeth Manchester of the Manchester Store in Adamsville related a

story her father told her of Perry Davis shopping in the store. Charlotte

White — "one of the store's best customers" — concocted a mixture

of food coloring, herbs and rum "which she sold to the temperance people

of Westport and Adamsville as a medicine." (A Temperance pledge meant

total abstinence from alcohol, but "medicine" was okay.) Charlotte bought

the rum at the Adamsville store. On his rounds selling peppermint and spices

around Westport, On The Town 'Payroll' Town financial

records indicate that Charlotte White was involved in poor relief before the

almshouse was established in 1824. The records reveal that "Cholata White" was paid for keeping Amy Jeffrey in

1812. The following year she received $34.24 for keeping Jeffrey, plus an

additional $13.43 "to Cholata White's account,"

presumably for other poor relief. In 1816,

Charlotte was reimbursed for keeping Henry Pero, a black child, two weeks and

two days old, and also received $2.86 for making clothes for him. (Henry Pero

was later cared for by Mary Wainer, Paul Cuffe's niece.) In 1818 and 1819,

Charlotte took in both Deborah Pero and her young son. In a remarkable entry

in the town records for 1818, she was paid for "keeping Nursing and

doctoring" Deborah Pero for 14 weeks. The use of the term

"doctoring" in the official records gives credence to her

reputation as a healer. This isn't just

folklore: Charlotte White took in and treated poor or troubled people, before

the almshouse was established, and was reimbursed by the town. At least some

of the paupers she cared for were people of color. Unfortunately there is

nothing in the records about her role as a midwife. “A recently

unearthed newspaper article from the 1940s links Charlotte to another

noteworthy Westport native, Perry Davis. Davis (1791-1862) achieved great success

as the manufacturer of Perry Davis Pain Killer, one of the best-selling

patent medicines of the 19th century. The success was largely due to his

secret formula of vegetable extracts, alcohol, and opium. Perry Davis met

Charlotte White and tried her medicinal brew, and according to Mrs.

Manchester, this is where he got the idea for his famous pain-killer.” Tony Connors, WHS Mystery Photo There is no

definitive image of this elusive woman. In the Historical Society collection,

there is a photograph of a woman purported to be Charlotte White, driving an

oxcart. As much as we would like it to be her, it is unlikely. Charlotte

lived into the age of photography, but the telegraph pole in the background

of the photo suggests a date beyond her lifetime. Charlotte died on

June 17, 1861, at the age of 87, of "lung fever" (probably

pneumonia). She is buried with her parents in a private cemetery behind 165

Charlotte White Road, near the site of their former home. Charlotte White is

an intriguing character from 19th century Westport, with connections to

Native American and African American history, slavery, poor relief, folk

medicine, and midwifery. This is what we

know about her — certainly not enough — and I hope we can continue to fill

out her life story. If you have any information that adds to or corrects what

is presented here, please contact the Westport Historical Society at

508.636.6011 or by e-mail to: westporthistory@westporthistory.net. |

|

|

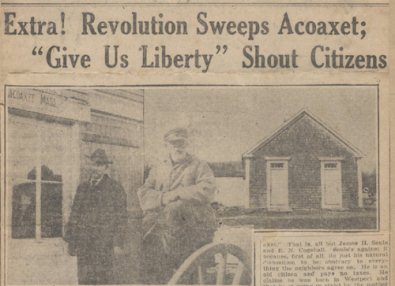

‘Secession!

– July 22, 2012 In the 1920s, the Westport Harbor

section (of Westport, MA) made two serious attempts to separate from the rest

of the town, and to form a new town called Acoaxet. Presented by Tony Connors, President, Westport Historical Society. Editor’s note – There have been many

secession attempts after the Civil War. Since the election of President Obama the White House website reveals that there are

currently over

40 petitions (states) that have requested the secession of their state

from the Union. However, these petitions are not made by the State

Governments of each state, but of those who are John Doe Citizens of that

state. More than 750,000 Americans have

petitioned the White House website to let their respective states secede,

from Alaska to Iowa to Maryland and Vermont. Those leading the charge are

framing it, observers say, in terms that suggest a deep-seated religious

impulse, for purity-through-separation is flaring up once again. Secession petitions are not a rare entity in America,

but Westport Harbor’s challenge was novel and entertaining to those of us

today who realize the only sure things in life are death and taxes!

Geography played a big part in this affair.

Back when Westport was part of Dartmouth, the land in question had been

claimed by Plymouth Colony, but Rhode Island’s 1663 royal charter specified

its eastern border as “three English

miles to the east and north-east of the most eastern and north-eastern parts

of Narragansett Bay.” Since no one could agree whether the Sakonnet River was

part of Narragansett Bay, both Massachusetts and Rhode Island contested the

border. In the 1740s Rhode Island appealed to the king – and the king agreed.

The newly drawn line separating the two colonies ran through Adamsville and

straight to the sea, isolating a part of Dartmouth from Little Compton and

Tiverton, and resulting in the odd fact that Acoaxet could only be reached by

going through Rhode Island. Although the state borders were again revised in

1861, well after Westport had separated from Dartmouth, the geographical

peculiarity remained. Westport Harbor developed in the late 19th

century as a summer colony. By 1920, when Westport’s population exceeded

3,000, the Harbor could claim only 127 year-round residents and 33 registered

voters, although the Harbor population more than doubled in the summer, as

wealthy Fall River families filled the hotels and seaside cottages. The best

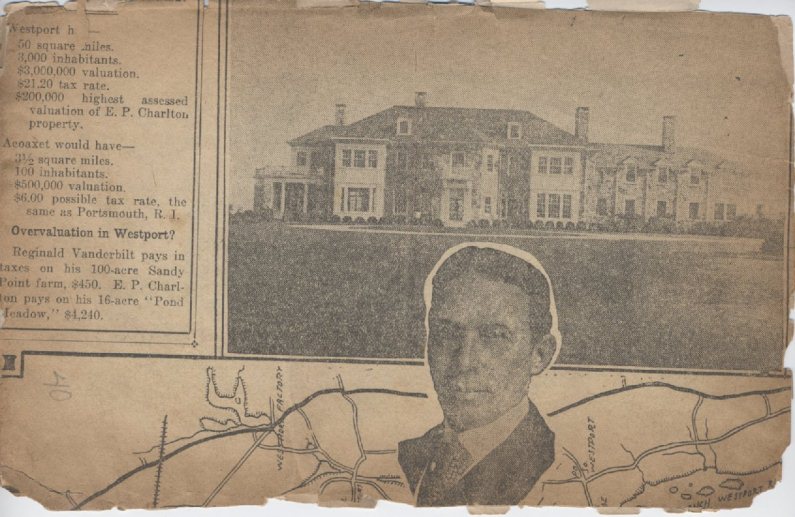

known of the summer residents was Earl P. Charlton who had made a fortune by merging

his “five and dime” stores with the F. W. Woolworth chain. Charlton’s Pond

Meadow – still an elegant mansion at the mouth of the Westport River –

generated more tax revenue than the Westport Manufacturing Company, the

largest employer in town. Charlton and a number of other Harbor residents

felt that they were paying too much in taxes for the paltry town services

they received. In January 1919, asserting inadequate police protection and

poor roads – and after their requests for tax abatements were denied – a

group of Harbor residents appealed to the state Legislature to separate from

Westport and form a new town called Acoaxet. The disruptive times of 1919 probably added

to the dissatisfaction of the petitioners. World War One had just ended (with

15 million deaths worldwide), and now an influenza epidemic was raging – and

would eventually claim 100 million casualties. The divisive issues of

Prohibition and women’s suffrage were also decided in 1919. The world, it

seemed, had turned upside down. The Harbor’s secession petition was heard

by a state legislative committee in Boston. One important witness was

District Court Judge James M. Morton Jr., a summer resident of Acoaxet, who

testified that Harbor taxpayers were exploited by the town and that having to

pass through Rhode Island posed problems of legality for the police. The

Harbor petitioners estimated that over the past ten years they had paid

$70,000 in taxes but received only $20,000 in services. The one-room Acoaxet

schoolhouse (with 13 students) was woefully inadequate. While this was going

on, the rest of Westport had their say: every section of town complained

about taxes and anyway it was the state that demanded higher property

assessments, mostly on waterfront property. Furthermore, the Harbor was

simply too under-populated to be a legitimate town. As for the school, Acoaxet’s was no worse than the others: the School

committee reported that they were all deplorable. At a special town meeting

in January 1919, the vote was 139 to zero to oppose the secession. But the

state committee let the matter rest and Westport Harbor remained in Westport.

In January 1926, the Acoaxet petitioners

again brought their request to the state Legislature. Coincidently, two

secession petitions in Dartmouth – one group wanted to form a new town, and

another wanted to join New Bedford – were also being considered by the

Legislature. In Westport Harbor the grievances were essentially the same as

they had been seven years before: inadequate roads, school, and police protection;

physically separated from the rest of Westport; and a disproportionate share

of town taxes. As the petitioners’ attorney John W. Cummings put it:

“Westport looks upon Acoaxet as Rome looked upon her provinces, as a source

of revenue.” Westport’s attorney, Arthur E. Seagrave,

rose to the challenge. Any town might have a section that pays more in taxes;

in fact, Massachusetts and New York could secede from the Union for paying

more taxes than poorer states. “This is false logic and one charged with dynamite.”

He conceded that Acoaxet did not get its share of poor relief, because no one

there was on poor relief, or as much in school expenditures, because they had

only three percent of the total school population. Therefore it stood to

reason Harbor would not get back all that it put in. Furthermore, separation would leave

Westport with more than its share of public debt: the town tax rate would

climb to $40 per thousand, while Acoaxet’s would

drop to $10. Attorney Seagrave concluded with an appeal for Harbor residents

to “Remember that Acoaxet was a part of Westport when Acoaxet was a howling

wilderness … and other portions of Westport made their sacrifices to provide

roads and a school for this meager settlement.” Now, automobiles have changed

all that and a newly affluent Acoaxet would “leave her old parent with heavy

burdens to bear.” While the issues were being hashed out at

the state level, Westport held a special town meeting on March 9. Over 300

citizens attended – the largest number ever seen. The focus was on taxes. As

Dr. Breault put it, “Taxation is a worldwide

problem. There isn’t a city, a town, or a hamlet throughout the length and

breadth of this land that hasn’t its problems. Acoaxet has its grievances. So

have South Westport and Central Village and every other section of the town.

There is no spot on earth where the question of taxation is not a problem.”

Added to the dispute over tax fairness was an

underlying resentment that had carried over from the World War. It was

exemplified in a poem by Bill Potter, which he read at the town meeting. It

went, in part: The boys received a dollar a day While it did represent the feelings of many

of the town meeting participants, the poem did little to raise the level of

the argument. However, it was not up to town meeting to decide: all waited to

hear the decision of the legislative committee in Boston, which met on April

1. Again Judge Morton and Richard Hawes spoke eloquently for separation, but

the committee reported unanimously against the separation of Acoaxet from

Westport. The ostensible reason was that Acoaxet would have too few voters to

operate as a separate town. There may also have been a general aversion to

breaking up established towns: the two separation petitions in Dartmouth were

also denied. The matter quickly faded from town records

(although perhaps more slowly from the minds of the participants). Soon

enough there were other pressing issues to worry about: Prohibition and

rum-running, the Great Depression, the devastating hurricane of1938, and

World War II. Almost a century later, how should we look

at the attempted secession – as a historical curiosity, or as an event that

might have some relevance today? Certainly it reminds us that Westport has a

long history of village loyalty that is both part of its charm and a

potential source of friction. The end result of the 1920s dispute is that For more information about this article

contact Jenny O'Neill, Director at the Westport Historical Society, PO Box

N188, Westport MA 02790; call 508.636.6011; or email westporthistory@westporthistory.net. Visit their website, or

like them on facebook. Photos courtesy of Westport Historical Society |

|

|

Westport Historical

Society releases Handy House Cookbook. October 4, 2011 - The Handy House Cookbook is ready just in time for holiday giving.

Published by the Westport Historical Society, this book honors Eleanor Tripp,

Westport’s unofficial historian and the last resident of the Handy House. All

proceeds from the sale of this special cookbook will support the restoration

and preservation of the Handy House by the Westport Historical Society. Besides

researching Westport's history, Eleanor, who loved to cook, collected a vast

number of recipes. This book includes over 200 of her tasty recipes, along

with a dedication to Mrs. Tripp and a little taste of Handy House history.

The Handy House is a unique architectural time capsule that embodies the

first three principal architectural trends to occur in this nation’s history,

as well as representing the story of everyday life in Westport over the

course of three centuries. Norma

Judson, who has spent many hours selecting recipes for the cookbook,

described Eleanor as the “Queen of Flour.” The fragrance of baking bread and

simple dishes were always wafting from the Handy House. She loved to cook

simple, basic recipes. Her kitchen was primitive and she often used her

fireplaces and she shunned microwaves. The baker

will find recipes for over a dozen varieties of yeast breads (some with a

Swedish flavor, reflecting Eleanor's Scandinavian origins), plus quick

breads, muffins, cookies and cakes. Locavores will appreciate Eleanor's

emphasis on local vegetables, seafood and good soups. They will find close to

20 veggie dishes and almost as many soups. Remember the casserole? Some of

these main dish favorites are revived here.

Designed by

Geraldine Millham, the cookbook also includes many

photographs of the historic Handy House, as well as information about the

significance of the property. The Handy

House Cookbook is available for purchase ($19.95 plus tax) at Partners, Lees

Market, and the Westport Historical Society. More information including an

order form is available at www.westporthistory.com or by calling 508 636

6011. The Handy House Cookbook is funded by the Westport Cultural Council

through a grant from the Helen E. Ellis Charitable Trust administered by Bank

of America.

+enlarge Photos courtesy of

Westport Historical Society |

|

|

Westport’s

oldest weekly newspaper revealed in Historical Society find.

- June 28, 2010 The

1896 weekly newspaper shown in the photo below may be an ancient ancestor to

today’s Westport weeklies - Westport Shorelines and Dartmouth/Westport

Chronicle. The only known copy of the Westport

News is in the archives of the Westport Historical Society. “We

don’t know much about the Westport News,” said WHS Director Jenny O’Neill.

“If anyone out there has additional copies or more information about the

company “The

weekly paper appears to have been first published in the fall of 1895, and

there is no knowledge of when it ceased operation.” O’Neill said. +enlarge The

format of the weekly suggests that many versions of the same paper were

published with the names of different towns printed in the front page blank

header space. A

form of this concept is still used today in a slightly more sophisticated way

by the East Bay Newspaper group which includes Westport Shorelines and

Sakonnet Times with other Rhode Island weeklies (Barrington, Bristol, Warren,

Portsmouth, Little Compton, Tiverton, and Westport) which share stories and

advertisements, with a smattering of local interest stories and news in each variant. A

consolidation of resources (reporters, photographers, print facilities, and

advertisers) made this concept financially viable while still reaching out to

smaller markets. The

editors also wrote articles about local businesses, probably hoping for their

advertising dollars much the same as they do today, As

with all weekly newspapers, the internet poses a formidable threat through

reduced advertising revenue, and may bring an end to this folksy print

media. Other area

newspapers of the time. The

Standard-Times was formed from the 1934 merger of The New Bedford Standard

and The New Bedford Times. The Standard had been in operation since +enlarge Three

Fall River newspapers combined in 1892 to form The Herald News: the Fall River

News, which dated from 1845; the Fall River Daily Herald, 1872, and the Fall

River Daily Globe, 1885. Fall River Herald

07/11/2010 – Westport Historical

Society finds old newspaper, seeks information on its origin. The Historical Society

has discovered an old weekly newspaper from 1896 called Westport News but

can’t find any other information, like who published the paper and for how

long. “I’ve never heard of it until we just happened upon it,” said Jenny O’Neill, the Historical Society director. Click here to read more from Herald article. Photos by

EverythingWestport.com |

|

|

Life Saving Station’s lantern returns home. - December 12, 2009

Mr. James Panos of Westport donated to the Westport Historical

Society the brass oil lantern (once converted to electric but now restored)

that was given to him by Henry

Brown of Rhode Island, an avid collector of antiques. Brown found two

lanterns in a Maine barn. In a chance meeting with Panos at a conservation

group get-together, the two struck up a conversation and the rest is history.

Brown authenticated that it was indeed an original lantern that hung in Life

Saving Station No. 69. The lantern is on loan to the Life Saving Station Museum by the

Westport Historical Society. Photo by

EverythingWestport.com |

|

|

Billy

Albanese of Albanese Monuments at 303

State Road in Westport recently applied some good old fashioned elbow grease

with a stiff-bristled brush and water to restore the patina to the Captain Paul Cuffe granite monument

near the Friends’ Meeting House at 930 Main Road in Central Village. “You

can’t power-wash or steam-clean these old stones,” Albanese said. “That could

damage the surface.” The

monument was cleaned in preparation for Cuffe’s

250th birthday celebration this June. “I used a mild acid to kill the

lichens, moss, and other green things growing on the surface,” Albanese said.

“Just scrubbing off that growth without the acid would allow it to grow back

in four to five years.” Albanese

pointed out that you shouldn’t attempt to clean a memorial stone yourself as

its surfaces are porous, and the wrong cleaners can severely stain the stone.

“Even the mild acid I used could damage the stone if not properly handled,”

he said. Want to clean your beloved’s monument yourself? “Water, a stiff-bristled brush (no metal

please) and lots of elbow grease,” Albanese advised. According

to the Westport Historical Society, the Cuffe monument was dedicated June 15,

1913. Photo by

EverythingWestport.com |

|

|

This

traditional-style federal house was the site of the first Town Meeting in

Westport after the town legally separated from Old Dartmouth in 1787, just

three years after the birth of our new nation. At the time it was the William

Gifford property. An 1850 Westport map shows it later belonged to Richard

Gifford. Located at 1074 Main Road, it was demolished in 2002 and is now a

field. The

photo to the left is the last known for this property (circa 2001). According

to the Westport Historical Commission, while the new Town House was being

built where the St. John’s Church Parish Hall on Main Road now exists,

additional meetings were held in the old Mary Hick's Tavern on the southwest

corner of Hix Bridge. Photo

by EverythingWestport.com |

|

|

First

European built house in Westport: the Waite-Potter House - February 15, 2009 Your

first on-site visit to the Waite-Potter restoration site will be

monumental. The remains of the original homestead are much more than the

small chimney you’d imagined. It is the entire west wall of the house! An enormous

structure of field and quarried stone, and mortar. It’s a true memorial to

the 1670’s house that may be Westport’s earliest known European-built

structure. Read

the article with photos on the Waite-Potter restoration now! The Waite-Potter house was mostly destroyed by

Hurricane Carol in 1954. The Waite-Potter site is on private property.

Please respect the owner’s privacy. Photo on

left by EverythingWestport.com

Photo on right courtesy of Muriel

(Potter) Bibeau. |

|

|

|

Historical Westport Grange stage curtain revealed! - December 15,

2008 This

past summer, Westport Grange No. 181 took a wonderful old theater curtain out

of “moth balls” and displayed it on stage during the Farmers’ Market and most

recently at its Christmas Fair. The curtain had been stored vertically flat,

high in an eave pocket, accounting for its pristine condition. But

this is no ordinary stage curtain. During the great depression granges, like

everyone else, were suffering financially. The stage curtain provided an

advertising medium to help generate needed funds to support the grange’s

activities. The ads give us a historical perspective of Westport businesses

in the 1930s. The

blank curtain backdrop was originally painted by A.H. Chappell in 1931. We

have no information at present about Chappell. It is thought, but not known,

that the first ads were painted at the same time. New ads (the ones in white)

were painted over the old ads by Sam Hadfield (Marie Hadfield’s husband) in

1951. Cukie Macomber recalls the advertised companies. Photo by

EverythingWestport.com |

|

Photo courtesy of Barbara Hart of Westport |

The Head of Westport flooded by Hurricane Carol in 1954 - October 15, 2008 Westport

is now being threatened with a host of fall storms starting with Hurricane

Hannah, and followed by her evil siblings Ike and others. The building now

housing Osprey Sea Kayak and the old Head Garage now owned by Dan Tripp are

shown in the photo’s center. The building to the right is long gone. |

|

Photo courtesy of the Westport Historical Society |

J.

M. Shorrock & Co. general store at the Head of Westport – August 17, 2008 Originally

the country store of Charles A. Gifford built in 1889, and last owned by

Joseph Shorrock prior to 1900, Shorrocks

was believed to have been torn down in the 1930’s, and rebuilt to the current

concrete block structure found there today. This location is the new home of The Head Town Landing Country Store. Ron

and Sue Meunier of New Bedford ran the R&S

Variety head store for 31 years, and retired in August, 2008. Rory and

Kathy Courturier of Westport are the new proprietors. Read the story

of the new Head store now! |

|

Photo courtesy of the Westport Historical Society |

The

Hurricane of ’54! – July 18, 2008 Rescue

at the Point – 1954 hurricane. Laura’s

restaurant is seen in the background floating away! “I

was back at the Beach early that morning.

The East Beach was utter desolation.

Not a building the whole mile length of it. The West Beach was a drunken man’s

nightmare - houses toppled about in all stages of wreckage. We from the West

Beach thought we had a harrowing night.

But we had the safety of the dunes.

For those on the East Beach there had been no retreat. The Let engulfed them - men, women and

children.” – Unknown author. |

|

Photo by EverythingWestport.com |

The

Wolf Pit School restoration - June

15, 2008 In

May of 2005 the Community Preservation Committee won approval at Town Meeting

to restore the Wolf Pit School (also called the Little School), the last

remaining one-room schoolhouse in Westport. This remarkable achievement was

only surpassed by the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Calvin Hopkinson (pictured

left) and their children, the owners. It is the “best and last of our public

buildings from the 19th century”. Read

the whole story about the restoration. View photos now! 183 photos | Dial-up speed | Broadband/DSL speed | |

|

Photo by EverythingWestport.com |

We’ll

keep the light on! - April

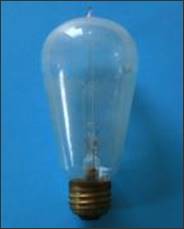

29, 2008 The

light bulb pictured left, 4 ¼ inches tall, was the first light bulb to be

installed at the Acheson farm at 1 Old Horseneck Road circa 1922 when

electricity first came to Westport. It was installed in the house’s front

entrance and remained there in use until 1989. It was donated to the Westport

Historical Society in March of 2008 by Elizabeth Acheson. The bulb is a

General Electric National Mazda, wattage unknown, but probably 25 watt, 115

volt. It has a filament of six loops. On

December 21, 1909, General Electric first used the name Mazda on their lamps.

The name was trademarked, and assigned the number 77,779 by the United States

Patent and Trademark Office. Today, we associate the name with automobiles,

but when it was first used by GE it was chosen to represent the best that the

American lighting industry had to offer at the time, and was selected due to

the fact that Persian mythology gave the name Ahura Mazda to the god of

light. The

genius of today’s light bulbs is not in their shape or size, but in their

light-producing core. The first light bulbs used carbon rods to conduct

electricity. They produced inconsistent light output and were short-burning.

In 1879 Thomas Edison used carbonized bamboo for the filament, resulting in a

bulb that was cheaper, more muted, and longer-lasting. Output consistency was

still a problem, however. The

General Electric Company, in 1906 was the first to patent a method of making

tungsten filaments for use in incandescent light bulbs. Click on the image to enlarge. |

|

Photos by EverythingWestport.com |

Westport

River Herring Dam – March 31, 2008 In a recent conversation with Staff Hart, Westport Landing

Commissioner, EverythingWestport.com

came to learn about the “herring

dam” on the East Branch. What’s this, another dam on the Westport

River? “When we were kids,” Mr. Hart said, “we used to walk out on the rock

dam and string our nets behind one of the dam’s two sluices to catch the

herring. The dam has been there for as long as I can remember.” Mr. Hart is referring to the loosely-built, fieldstone dam built

across the Westport River about 75 yards north of Old County Road. Quentin

Sullivan was kind enough to allow us to walk across his property to view the

dam. “The heavy rains would knock over some of the rocks, but we

would put them back up again,” Mr. Hart said. “We caught a lot of herring

back then,” he said. “We would walk out on the rocks and cast our nets on the

waters!” Westport has several well-known herring runs, including River

Run off of Acoaxet off River Road, and the Albert Rosinha Herring Run at

Adamsville Pond. “Herring were plentiful years ago,” Mr. Hart said. The

Alewife (herring) were responsible for the final

approvals by the State of Rhode Island in 2007 in permitting the dredging of

Adamsville Pond by Ralph Guild. “If the alewife weren’t there, the pond would

not have been dredged,” Mr. Guild said. Left: The

“herring dam” washed over by heavy spring rains. Click on photos to enlarge. |

|

Community

Events of Westport © 2008 - 2019 All

rights reserved. |

|

|

EverythingWestport.com |

|